Will we soon have negative interest rates in the United States? This weird, upside-down condition wasn’t in economic textbooks and is a challenge for investors and financial advisors.

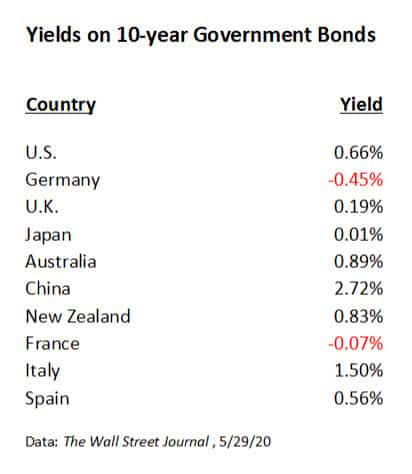

Negative interest rates have already occurred in Europe and Japan. More than a dozen countries are within 100 basis points of 0%.

Closer to home, the biggest local bank in Omaha pays just 0.05% for a basic savings account.

Do negative interest rates make any sense? How did they come about? What do they mean for the financial plans of Omaha investors and the way they should invest?

What Are Negative Interest Rates?

Don’t feel bad if you aren’t familiar with negative interest rates. Until a few years ago, even the people who make interest rate policy didn’t think they were possible.

When you buy a certificate of deposit, invest in a bond or otherwise lend money, you receive interest and the eventual return of your principal. Interest rewards you for giving up the present use of your savings. At the end of the loan period, you will have more money than you started with.

When you lend money at a negative interest rate, you agree that the combination of interest and principal you receive will leave you with less money than you started with.

Such a deal! Who wouldn’t want to lend on terms like that?

No one, of course. There has been a long secular trend toward lower interest rates. But negative interest rates are unnatural.

Unless they are feeling charitable, people expect interest when they lend. The money we have today can be used to buy things, make investments or save for the future. We don’t give up this flexibility for free, let alone for a negative return.

Why Do We Have Them, Even in Omaha?

To encourage spending and investment after the financial crisis of 2008-09, policymakers around the world cut interest rates dramatically. In the United States, it’s the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) that sets interest rate policy.

The Fed has bought huge amounts of bonds and other financial assets. From having $870 million in assets in June 2007, the Fed in early June 2020 had $7 trillion.

This buying by the Fed has driven up asset prices and reduced their potential return. For bonds, this means extremely low yields.

The Fed’s counterparts in Europe took things a step further in 2014 when they began to charge interest on the deposits that lenders held with them. This was an early example of negative interest rates.

The idea was that these institutions would rather make loans and earn interest than have to pay it. More lending would boost the economy.

Jump-starting didn’t really work

The monetary authorities thought that their policy of low interest rates would be temporary. When growth rebounded, interest rates would go back to normal.

But growth never became very strong, and policymakers worried that higher rates might lead to a recession. That would make it hard for indebted countries in Europe to pay their bills, and threatened the existence of the European Union.

But complacency seems so relaxing

Even though their policy of low interest rates didn’t work as planned, authorities stuck with it and have pursued it even more aggressively. In early April, $10.6 trillion of government debt around the world was priced at a negative yield. This was equal to 18% of total government debt.

In the U.S., the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jay Powell, has said a policy of negative interest rates “is not something we are looking at.” Futures markets, though, are pricing in a small chance that the Fed will implement such a policy within a year.

Officials in England have also hinted that negative rates are a possibility. They deny that such a step is being planned, but they say that they are keeping an open mind and are studying the matter.

You can understand why the Fed and other policymakers don’t want to change what they’re doing. Low interest rates are popular with consumers, business and politicians. Changing policies might cause problems.

Besides, they don’t see much downside to what they are doing. It’s not as if they are investing their own money when they buy bonds at prices that are unnatural for individuals.

The biggest fear of the low and even negative interest rates policy had been that inflation would become a problem. That hasn’t happened.

Meanwhile, people have gotten used to low interest rates, and complacency has set in. The economists who once thought negative interest rates were impossible now speak of them matter-of-factly as another option in their policy “toolkit.”

Why Would Anyone Buy Securities with a Negative Yield?

An analyst at Schroders suggests a few reasons that individuals might choose to buy securities with negative yields:

- Interest rates could fall even more, which would make bond prices rise.

- Traders can use sophisticated currency contracts to provide a higher total return.

So circumstances could lead a profit-seeking trader to buy securities with a negative yield.

But do individual investors see negative-yielding securities as something they want to buy? Do competent financial advisors in Omaha or elsewhere recommend them as good investments?

Here’s the main reason investors buy such issues: They don’t have much choice.

How so?

The trouble with cash

Economists used to think that negative interest rates wouldn’t happen because people would choose to hold currency instead of securities. Currency pays no interest, but that’s better than a negative return.

Small savers can choose to hold currency, but they face two big problems:

- Currency can be lost or stolen. Savers need to buy protection, whether a safety deposit box, home security system or something similar.

- It’s getting harder to use cash. The war on terrorism imposed reporting requirements on big cash transactions. Many businesses and organizations won’t accept cash payments anymore.

But the fact that small savers can convert some of their deposits into currency is one reason that financial institutions have been reluctant to charge negative interest rates on small deposits.

Large depositors find it impractical to use cash, and they have been charged negative interest rates. In response, they try to minimize their cash holdings, which can include investing in riskier assets.

Who Is Helped By Negative Interest Rates?

The fan base for low and even negative interest rates is huge, even in Omaha. Low rates tend to encourage business activity and raise values in the financial markets. When people are happy, life for policymakers is good.

Business

Low interest rates make it cheaper to expand operations and invest in new ventures. Companies that are heavily indebted can refinance at low rates.

Consumers

When business activity picks up, jobs and incomes rise. Low rates may make it worthwhile to refinance mortgages and other debts. Buying goods and services on credit is easier.

Investors

Prices of financial assets often rise when interest rates fall. Policymakers hope that this “wealth effect” will encourage investors to spend, thereby helping economic growth.

Non-Profits

Non-profits aren’t usually mentioned as a beneficiary of low rates, but they are. Economic growth and strong financial markets encourage donations. Building projects are easier to afford. If a non-profit has a foundation, the value of its financial assets will likely benefit.

Government

Lower rates make it easier to finance deficit spending. To the extent that business activity goes up, tax receipts will increase.

Who Is Hurt?

Low or negative interest rates do hurt some groups, but this usually gets little attention.

Savers who want income and low risk

Retirees who might have bought CDs to supplement their Social Security income are hurt by low rates. They may have to go back to work or spend what savings they have on living expenses.

Investors who are wealthier and more diversified may find that the lower interest they receive from money market investments is offset by appreciation from other investments.

Pension funds with more liabilities than assets

To make sure they have enough money to pay future expenses, pension funds estimate a rate of return they will make on their investments. If actual interest rates are lower than expected, the pension plan may go into deficit. Contributions to the plan may have to rise or benefits may need to be cut.

Lenders

Financial institutions make money by paying low rates to depositors and charging higher rates to borrowers. This spread can be squeezed at low rates because these institutions are reluctant to charge negative interest rates to small depositors.

Lenders face the prospect of simply charging less for loans and making less money.

The prospect of earning a lower spread on loans will tend to make lenders reluctant to extend credit. The risk of non-payment may be too great to make it worthwhile.

Because of this, policymakers may not see the sort of increase in lending that they hoped would result from a rate decline.

Insurers with long-term liabilities

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners notes that life insurance companies may not be able to earn enough from their investments to pay benefits they promised to policyholders. More broadly, these companies face challenges to their earnings, capital, reserves, liquidity and competitiveness.

Money market funds

Fund management companies make money by keeping part of the income from the securities they manage. If rates fall too far, they will find it unprofitable to stay in business.

What Are the Risks of Negative Interest Rates to an Investor in Omaha?

The Federal Reserve and its peers continue to follow a low interest rate policy despite the potential for bad consequences.

Among the possibilities:

Risk-taking becomes excessive.

This takes many forms. I’ll mention three:

- Malinvestment. Business investment that looked good when rates were low may look terrible when interest rates rise to a more normal level. New commercial real estate projects in Omaha may not pay off.

- Reaching for yield. Investors looking for higher income may invest in riskier things that they don’t really understand. A typical example is buying a stock with a high current dividend yield without realizing that the dividend may be cut.

- Scams. Closely related to reaching for yield is the attraction of too-good-to-be-true investments. Promoters can take advantage of people who overlook risk when looking for a high return.

Federal spending is unrestrained.

When is the last time you heard a discussion about balancing the federal budget? It no longer seems necessary. Investors used to be concerned that heavy borrowing by the Treasury Department would “crowd out” private borrowing and drive up interest rates.

Federal Reserve buying of Treasury securities has so far prevented any noticeable crowding out. Politicians on the left and right see little reason to worry about budget deficits when interest rates are low.

Warren Buffett suggested at the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting that this state of affairs won’t last:

“I would say this, if you’re going to have negative interest rates and pour out money and incur more and more debt relative to productive capacity, you’d think the world would have discovered it in the first couple thousand years rather than just coming on it now.”

Interest costs on government debt may explode.

Declining interest rates have softened the impact of a huge increase in the federal budget deficit. If rates were to increase, interest charges on the debt would skyrocket.

The Manhattan Institute published a report in February that cited a forecast of interest expense prepared by the Congressional Budget Office. Interest expense is expected to go from 1.8% of the size of the economy to 7.6% by 2049.

At that point, interest expense would be the biggest budget item, taking 42% of all federal tax revenue. Interest expense would far exceed the cost of Social Security.

This forecast was done before spending on Covid-19 raised the budget deficit even more. It also assumed that interest rates stayed in a range of 3-4%.

If interest rates began to return to a more normal level, the financial markets would quickly anticipate some combination of higher taxes, reduced spending, “crowding out” of private investment and accelerating inflation.

Inflation may come back.

Various explanations have been offered for why reported price increases have been low in recent years.

But Fed officials say plainly that they want inflation to rise to 2% – or even higher. They may eventually get their wish.

Policymakers like inflation for two reasons:

1. Inflation encourages consumers to buy now rather than face higher prices tomorrow. Policymakers like this because it spurs economic growth in the short-run.

2. Inflation reduces the burden of government debt. A fixed amount of debt can be repaid with dollars that are worth less in real terms.

Officials expresses confidence that they can contain inflation to a rate they want, but the complexity of the global economic system makes it hard to believe that they can.

On top of this, if the Chairman of the Federal Reserve said he favored higher rates, he would be severely criticized. This prospect is bound to make him reluctant to act, which could make inflation worse.

It looks dumb to save.

Kids used to learn the “miracle of compound interest” by opening a savings account and seeing how interest made their deposit grow. With low or negative interest rates, it’s hard to convince anyone that saving is a virtue.

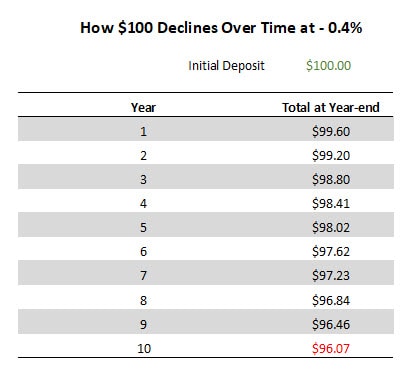

Imagine the reaction of a child who sees his account grow at the – 0.4% rate of a 10-year German government bond. A $100 deposit steadily loses money, becoming a little over $96 in 10 years. Thanks for nothing, mom and dad.

Governments are becoming owners of companies.

To meet their objective of driving down interest rates, policymakers have been willing to buy an increasingly wide range of financial assets.

One problem is that when authorities buy stocks, they become part-owners of the companies. The Swiss monetary authority, for example, owns hundreds of US companies, including Apple, Disney, General Electric and McDonald’s.

It’s inevitable that governments will use their ownership to promote political ends that differ from what the companies would otherwise do. That will pressure share prices.

What Should an Investor in Omaha Do?

Financial advisors and planners in Omaha and elsewhere commonly recommend that conservative investors put a large portion of their investment portfolio in bonds. The idea is to provide income and safety of principal.

But when interest rates are lower than they’ve been in 5,000 years, it doesn’t take much of a skeptic to question the wisdom of this advice.

If it’s overpriced, an investment is not conservative.

1. Avoid long-term bonds.

The risk/reward payoff for bonds is terrible. Income is virtually nil in absolute terms, and it’s negative once inflation and taxes are taken into account. A rise in rates would smash prices.

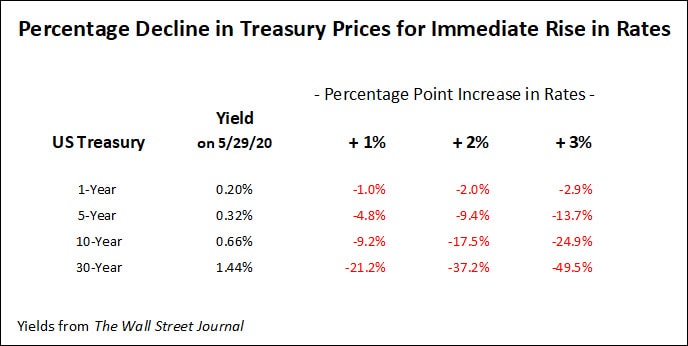

The table shows what would happen to the prices of US Treasury securities if market interest rates were to rise immediately by 1%, 2% or 3%.

As an example, the 10-year Treasury bond was recently priced to yield 0.66%. If investors demanded a yield of 2.66% – say because of a worry about inflation – the bond would drop in price by 17.5%.

Notice that price risk increases as maturities go up. A 1-year Treasury has much less price risk than a 30-year bond.

The investor in the 1-year issue won’t have to wait long to be repaid his principal. He will then be able to invest at the new, higher interest rate. An investor in the 30-year bond has to wait a long time.

If you invest in corporate bonds, it’s likely that your losses would be higher. Unlike US Treasuries, corporate issues have credit risk – you may not be paid what you’re owed.

2. Be willing to hold cash.

The only thing worse than no return is one that’s negative. Cash earns practically nothing today, but the risk of loss on bonds is very high. When more favorable opportunities are available, cash will provide the buying power.

3. Be selective when buying stocks.

Favor companies that don’t rely on borrowing or the sale of additional stock. Companies that rely on the market for funding may have to do so when it’s very expensive.

Also look for businesses that can do well during periods of inflation. This means that they can pass along price increases to their customers. The most attractive companies don’t require a lot of expensive investment to support current operations.

Read more about how we select investments for our clients.

4. Consider what this all means for your financial plan.

A financial plan is foolhardy if it assumes that bonds today are the foundation of a conservative portfolio. Your plan needs to be flexible enough to account for extremes in pricing. Bond prices are too high for them to be considered conservative.

- We are price-conscious, and we’re pleased to offer the services of two CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professionals, Matt Holloway and Katerina Wiese.

- Learn more about our entire approach to financial planning and investment management.

- Read more about financial planning and what you should know in our post “10 Better Questions to Ask Your Financial Planner in Omaha.”

Barry Dunaway, CFA®

Managing Director

America First Investment Advisors, LLC

Omaha, Nebraska

This post expresses the views of the author as of the date of publication. America First Investment Advisors has no obligation to update the information in it. Be aware that past performance is no indication of future performance, and that wherever there is the potential for profit there is also the possibility of loss.